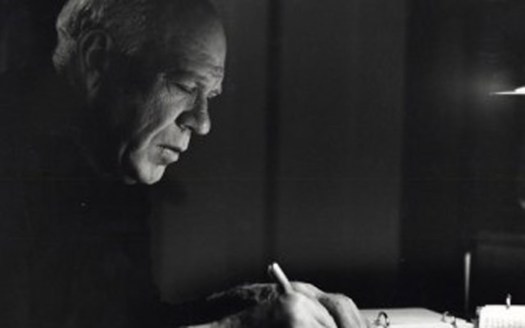

Hoffer lives in one room in a Chinese section of San Francisco. No telephone or television, no easy chair. It only has his own files, a few books, and a folding desk. Retired now as a longshoreman, he walks almost every day through Golden Gate Park about two and a half miles. He sees or hears some little things. An idea begins to be born, he may jot down a short note about it. A special set of muscles in his brain holds his idea that we find it may be for a week, a month, a year before he writes it out in a paragraph.

I believe this book is a timeless piece of masterwork written by the “Longshoreman Philosopher”: Eric Hoffer. Before dwelling into the content and the notion of the book, what amazed me was how self-deprecating he was when he was called Intellectual. He insisted that he was simply a longshoreman who work hard and long hours, but continued to read and scribble his thoughts into his pocket notebook. He once wrote: “My writing is done in railroad yards while waiting for a freight, in the fields while waiting for a truck, and at noon after lunch. Towns are too distracting.” He was deeply influenced by his modest roots and working-class surrounding.

Hoffer came to public attention with the 1951 publication of his first book, The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements (I’ve long wanted to read the book, and it seems the local bookstore does not sell Eric Hoffer’s books. I manage to get another of his book from a friend who sells used book which published in 1953 and the book condition is yellowish and obsolete.) In the book, True Believer, Hoffer analyzes the phenomenon of “mass movements,” a general term that he applies to revolutionary parties, nationalistic movements, and religious movements. Hoffer argues that fanatical and extremist cultural movements, whether religious, social, or national, arise when large numbers of frustrated people, believing their own individual lives to be worthless or spoiled, join a movement demanding radical change. But the real attraction for this population is an escape from the self, not a realization of individual hopes. True Believer was widely recognized as a classic, receiving critical acclaim from both scholars and laymen.

As for this book is a collected paragraph written in an aphoristic style which analyzes the human passionate mind and other aphorisms. He argues that passions usually have the roots of self-dissatisfaction which constantly struggles to face the inner being of oneself: “A mass movement attracts and holds a following not because it can satisfy the desire for self-advancement, but because it can satisfy the passion for self-renunciation.” He argues that men are constantly trying to assert and prove by whatever means to readjust the individual for self-assertion. People will prove themselves by winning medals, citations, degrees, and rank. We acquire a sense of worth either by realizing our talents or keeping our busy or by identifying ourselves with something apart from us –– be it a cause, leader, a group, possessions, and the like. But paradoxically, Hoffer believed that rapid change is not necessarily a positive thing for a society and that passionless can also cause a regression in the society which peaceful is somehow society is not hungry for growth: “For all we know, the wholly harmonious individual might be without the impulse to push on, and without the compulsion to strive for perfection in any department of life. There is always a chance that the perfect society might be a stagnant society.”

“Know Thyself.” This maxim or aphorism has had a variety of meanings attributed to it in literature. But here, Hoffer argues that we are often the one who permanently confusing ourselves when in fact we are seized with a passion to be different from what we are: “Man’s being is neither profound nor sublime. To search for something deep underneath the surface in order to explain human phenomena is to discard the nutritious outer layer for a nonexistent core. Like a bulb, man is all skin and no kernel.”

This brilliant and original work of Eric Hoffer offers us a peculiar and fascinating perspective of view to an inquiry on the nature of oneself and the nature of the mass movements. Here are a few of my favorite aphorisms on social psychology and political science:

“The craving to change the world is perhaps the reflection of the craving to change ourselves. The untenability of a situation does not by itself always give rise to a desire to change. Our quarrel with the world is an echo of the endless quarrel proceeding within us. The revolutionary agitator must first start a war in every soul before he can recruit for his war with the world.”

“Action can give us the feeling of being useful, but only words can give us a sense of weight and purpose.”

“Man is eminently a storyteller. His search for a purpose, a cause, an ideal, a mission and the like is largely a search for a plot and pattern in the development of his life story–a story that is basically without the meaning of the pattern. The turning of our lives into a story is also a means of rousing the interest of others in us and associating them with us.”

“Rudeness seems somehow linked with a rejection of the present. When we reject the present we also reject ourselves–we are, so to speak, rude toward ourselves; and we usually do unto others what we have already done to ourselves.”

“It is a talent of the weak to persuade themselves that they suffer for something when they suffer from something; that they are showing the way when they are running away; that they see the light when they feel the heat; that they are chosen when they are shunned.”

“A social order is stable so long as it can give scope to talent and youth. Youth itself is a talent–a perishable talent.”

“The real ‘haves’ are they who can acquire freedom, self-confidence, and even riches without depriving others of them. They acquire all of these by developing and applying their potentialities. On the other hand, the real ‘have-nots’ are they who cannot have aught except by depriving others of it. They can feel free only by diminishing the freedom of others, self-confident by spreading fear and dependence among others, and rich by making others poor.”

“It has been often said that power corrupts. But it perhaps equally important to realize that weakness, too, corrupts. Power corrupts the few, while weakness corrupts the many. Hatred, malice, rudeness, intolerance, and suspicion are the fruits of weakness. The resentment of the weak does not spring from any injustice done to them but from the sense of their inadequacy and impotence. They hate not wickedness but weakness. When it is in their power to do so, the weak destroy weakness wherever they see it. Woe to the weak when they are preyed upon by the weak. The self-hatred of the weak is likewise an instance of their hatred of weakness.”

Thank you for reading…

Nice review of this forgotten book of Hoffers. It is more insightful and rich than it first appears. Thanks for reviewing.

LikeLike

Thank you for your comment, it meant so much to me.

LikeLike